English History and Language

Introduction

Describing the history of Britain means describing a history of invasions and invaders. In the course of the centuries, five different people coming from as different regions as ancient Gaul, Mediterranean Italy, Northern Germany, Scandinavia, and Normandy have invaded the British Isles, killing, ejecting, subjugating or mixing with whatever population they found.

To a varying degree, the invaders have left their mark on the tongues of the people. As a consequence, the language of the often subjugated population of Britain bears the imprint of Celtic, Latin, Germanic, Scandinavian and Norman-French tongues.

- 1. Introduction

- 2. "Romanes eunt domus"

- 3. Anglo-Saxons: From runes to the Latin alphabet

- 4. The Vikings

- 5. The road to 1066

- 6. 1066 The Battle of Hastings

- 7. The aftermath of 1066

The main focus of this reader is on the interplay between historic events and their effects on the English language. It provides an overview of English history from the 5th century onwards, beginning with the Germanic invasions, the rise of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and the Viking threats.

We will have a closer look at England in the decades before 1066, and follow the development in the centuries after the Norman conquest of England.

Standardwerke der Sprachgeschichte Sponsored external links

A History of the English Language

The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language

"Romanes eunt domus"

The Roman Emperor Honorius withdrew protection from the province of Britannia in 410 AD. Roman rule was followed by a period of instability, during which the native Celtic population could hardly defend itself against continuing raids.

Around 450 AD, according to popular legend, the Celtic king Vortigern called two German overlords, the brothers Hengest and Horsa, to help him fight against looting Picts and Scots. The brothers followed his wishes. They and their people settled in the area of Kent, but soon rebelled against the Celts.

This is the Age of Arthur, the Celtic, or British hero, who, though only dimly lit by historical records, came to be embellished by romantic imagination from the twelfth century onwards. He was stylized into the legendary king we know today.

The descendants of Hengest and Horsa were Angles, Saxons, and Jutes from the region of Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein. In the following centuries, they gradually conquered the country while either subjugating the native Celtic population or driving them into safe havens like Cornwall and Wales in the west, Scotland in the north and across the Channel into Brittany. These are the exact sanctuaries where the Celtic language had a chance to survive.

In the course of the Anglo-Saxon settlement, seven large kingdoms gradually emerged, later known as the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy. The Heptarchy included the following kingdoms: Kent / Sussex / Essex / Wessex / East Anglia / Mercia / Northumbria

The supremacy over England kept shifting from one kingdom to the other. West-Germanic dialects spoken by the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes in their areas of settlement led to the development of three major Old English dialect areas: the Kentish, Saxon and Anglian dialect.

Roman and post-Roman era Sponsored / external links

The Greek & Latin Roots of English, Fourth Edition

Roots of English: Latin and Greek Roots for Beginners

Roman Britain (Oxford History of England)

Anglo-Saxons: From runes to the Latin alphabet

The Anglo-Saxons were heathen and used archaic runes as their means of writing. Magical signs were cut into small pieces of beech wood, thence the German 'Buch(en)stabe'.

Early in the seventh century, missionaries were sent to England. They were part of the Gregorian Mission, initiated by Pope Gregory the Great. His plan was to send missionaries to Kent in the south of England, where they targeted mainly the Anglo-Saxon courts, nobles, and kings.

The Christian faith started to consolidate, large dioceses were established. Bishops and archbishops took their seat in Canterbury, Rochester, Winchester and elsewhere. The drawback of such a “top-down” way of conversion was that it relied heavily on the rather precarious position of kings and nobles. In unstable and turbulent political circumstances, kings and nobles apostatized and abandoned the new faith together with their subjects.

A second wave of missionaries had a different geographical origin and a different but more successful method of conversion. They came around the same time in the early seventh century from Ireland, which had been Celtic for ages but Christian for about a hundred years thanks to St. Patrick. Wandering Irish monks established several monasteries in England, among them the famous cloisters of Lindisfarne on the east and Iona on the west coast of Scotland.

Having established several bases, they started to work their way southwards. Their method was simple: as wandering monks, they hoped to get into close and personal contact with 'ordinary' people and pursue their conversion “bottom-up”, so to speak.

Two distinctly different methods of conversion were thus at work in England in the seventh century: one coming from the south concentrating on royals and nobles (the Gregorian Mission), the other one coming from the north via wandering Irish monks.

Soon, conflict arose between the Irish and the Gregorian mission concerning issues of church organization as well as aspects of theology and liturgy. The Synod of Whitby resolved these problems in 664, where the matter was decided in favour of the Roman Church. Thus, England came into closer contact with the European Christian community, which enabled the Anglo-Saxons to tap into intellectual and theological currents of the time. At the same time, England came into contact with the Latin alphabet. That the alphabet was introduced via the Church manifests itself in the fact that a large bulk of Old English literature, apart from less numerous pieces of pagan or secular works, was inspired by or was exploring Christian themes.

Anglo-Saxon influence Sponsored / external links

An Invitation to Old English and Anglo-Saxon England

After Rome (Short Oxford History Of The British Isles): C.400-c.800

The Cambridge Old English Reader

Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts: Basic Readings (Basic Readings in Chaucer and His Time

Place-Names, Language and the Anglo-Saxon Landscape

Anglo-Saxons and Old English

Old and Middle English c.890-c.1450: An Anthology (Blackwell Anthologies

Anglo-Saxon history and religion

Angleland: State-building & nation-forging in Anglo-Saxon England, 593 - 1002

Mission und Christianisierung [...] bei Angelsachsen und Franken im 7. und 8. Jahrhundert

Light to the Isles: Mission and Theology in Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Britain

The Celtic Way of Evangelism, Tenth Anniversary Edition

Recovering the Past (Celtic and Roman Mission)

The Vikings

These times were too turbulent to give people the opportunity to enjoy to a larger extent poetry or prose. As the ninth century approached, again the clamour of warfare and armies and the cries of the battlefields were heard. The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had been firmly set up at the end of the eighth century. Wessex had gained supremacy over the other kingdoms, when a new threat appeared on the shores of England: the Vikings. In the course of the Viking raids, they had already looted the monasteries of Lindisfarne (793), Jarrow (794) and Iona (795), destroying monastic libraries with their invaluable manuscripts written in the Anglian dialect.

The main raids took place half a century afterwards. In 865, the Great Army, or - as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle puts it - the mycel heathen or hæþen here, invaded England. A considerable number of mostly Danish and Norwegian warriors landed on the east coast in East Anglia, conquered York, then entered Northumbria and Mercia, on which they soon had a firm grip.

After having extinguished two of the seven old Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, they tried to make further conquests by heading south. They would have succeeded if there had not been Alfred, then King of Wessex (871-899/900), later called Alfred the Great. Several times he opposed the Danish army, which had split in two and was roaming the territories of the Anglo-Saxons.

Although the battles largely remained indecisive, an agreement was reached between the Danes and Alfred. England was divided diagonally, and the Roman strata Vitelliana (= Watling Street) which ran from London in the south-east to the north-west of England became the borderline. On the one hand, there was the Danelaw, where Old Norse was spoken and Danish kings reigned. This area included East Anglia, the eastern parts of Mercia and the Kingdom of York in the north.

The land that remained under Anglo-Saxon control had shrunk to Wessex, Kent, West Mercia, and the London area. Alfred's merits include not only the stabilization of the political situation but also the fact that under his active participation and patronage, the most influential Latin authors of the time (Boethius, Orosius, Pope Gregory, St. Augustin) were translated into the West Saxon dialect, thus supplying the population with vernacular literature of high intellectual standard.

For the development of the English language, it is important to remember that parts of the Danish army left England. They sailed across the Channel, entered the Seine river, raided the area and eventually even settled there. Rollo, their leader, swore allegiance to the French king Charles III (893-929) in 912, thus recognizing him as his overlord. In return, the Danes were granted land to settle on in the area later known as Normandy. Rollo became the first Duke of Normandy.

The Norsemen showed a remarkable linguistic ability to adapt to this new situation of living on foreign territory. Surrounded by French neighbours, they were completely romanised in the course of two or three generations, which means that they abandoned their north-germanic dialect and adopted French. Rollo was the great-great-great-grandfather of a Norman-French speaking Duke of Normandy called William, who, in 1066, set sails to cross the Channel, to win the title 'Conqueror' and to take possession of England.

The Vikings Sponsored / external links

Language and History in Viking Age England

History and Culture of the Vikings

Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings

Anglo-Saxon and Viking Britain

Alfred the Great: War, Kingship and Culture in Anglo-Saxon England

Alfred's Wars: Sources and Interpretations of Anglo-Saxon Warfare in the Viking Age

The road to 1066

While the Danish were romanised quickly when they settled in Normandy, a similar process of assimilation took place in England. As the remaining Danes and the Anglo-Saxons were living side by side for over two hundred years, sometimes in peace and sometimes in war, their languages, and cultures slowly melted into each other due to cultural exchange and social interplay, thus forming an almost homogeneous group under the leadership of Anglo-Saxon kings.

At the end of the 10th century, Danish and Norwegian pirates once again raided the English shores. They used to be paid off by King Aethelred, who thought it was better to pay than to fight. His policy of paying tribute soon proved to be expensive and ineffective, if not disastrous. Aethelred, whose name originally means “noble-counselled”, was soon nick-named unræd (= “unready”), which means 'ill-advised' or 'the one without counsel'. It turned out that bribing the pirates had left them only hungry for more. In 1013, under King Swein whose father had united Denmark and Norway into one powerful kingdom, the Danes once again entered their ships and set sail for England. After a series of victories against the Anglo-Saxon forces, King Aethelred fled to Normandy, where his wife Emma originally had come from. The Danish invaders occupied the English throne. Swein died soon after the conquest, and his son Cnut (1016-1035) became the first king of Danish origin on the English throne. He united England, Denmark, and Norway into one large and powerful kingdom. Meanwhile, Aethelred spent the rest of his life (he died in 1016) in Normandy. After Aethelred's death, his son Edward (1002/5-1066), who had been raised in Normandy and had spent most of his early manhood there, was waiting for the time to be restored to power on the English throne.

The opportunity for the reinstatement of a rightful Anglo-Saxon king soon arose. King Cnut died in 1035, and his sons Harold and then Harthacnute succeeded to the throne. The royal Danish line died out with Harthacnute's death in 1042. The English throne was vacant again. Now the rightful Anglo-Saxon king Edward, who had spent 25 years in Normandy, was called to England to be restored to power. Thus, in 1042, Edward (later called the Confessor), was elected King of the English. Due to his upbringing in Normandy, Edward was responsible for introducing Norman-French noblemen, culture, and customs into his court. The most obvious example of Norman-French influence before the invasion of 1066 is Westminster Abbey in London. The magnificent church was built at Edward's behest in Norman-Romanesque style by Norman-French architects. The church was consecrated only a few days before Edward's death in early January 1066.

All in all, "it is somewhat ironic that the last great monument of the House of Wessex was mainly a product of Norman culture."1 Since Edward had died childless, a new king had to be found. On 6 January 1066, one day after Edward's death, Harold, the son of Godwin of Wessex, leader of the most powerful of the English earldoms, was elected king, although he was not a member of the English royal house. The new Anglo-Danish king immediately began to prepare for confrontation, for he knew that his kingship would not go unchallenged. One person who was sure to lay claim to the English throne was Duke William of Normandy.

The Road to 1066 Sponsored / external links

Aethelred II: King of the English 978-1016

Edward the Confessor: King of England

Harold: The Last Anglo-Saxon King

William the Conqueror: The Bastard of Normand

William the Conqueror (English Monarchs)

1066 The Battle of Hastings

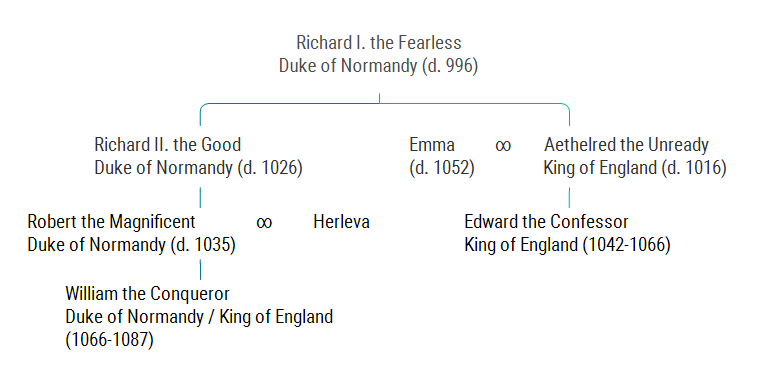

Unlike Harold, William could back up his claim with a certain though distant blood relationship to Edward the Confessor, the late king.

The pedigree illustrates several important aspects of William's life and his relationship to Edward. Foremost, they were related through Emma, King Aethelred's Norman wife. She was Edward's mother and William's great-aunt, i.e. his grandfather's sister, and this relationship made the Norman duke second cousin to the late King Edward. Secondly, the pedigree shows that William was illegitimate, a bastard child. He had sprung from his father's relationship with Herleva, a tanner's daughter from Falaise. The illegitimate birth somewhat complicated William's career, but at the same time made him used to overcome difficulties in life.

William had problems securing his own power over his dukedom of Normandy. When he succeeded his father as Duke in 1035, he was still a minor, a boy of seven years under the protection of his guardians. But as he grew older, his determination to secure his power over the dukedom of Normandy grew stronger, and he overcame conspiracies, rebellious barons and other difficulties. But fate also played a part in William's life. In 1064 or 1065 (we do not know the exact date), Harold went on a visit to Normandy. The purpose of his mission remains unknown. Some sources suggest that on that occasion, Harold fell into William's hands by mischance, was imprisoned and forced to swear an oath renouncing all claims to the English throne and granting William that right. Other (predominantly Norman) sources say that King Edward had sent Harold to Normandy as an ambassador to confirm Edward's own promise that William would succeed to the throne after his death. Whatever version is true, William felt he had a legitimate claim to the English throne, and behaved accordingly. When the news reached him that his rival Harold had been elected king, he began to prepare for a military campaign, gathering a well-trained army and a small fleet. William considered Harold as someone who had broken an oath, and for that reason "he appealed to the pope for the sanction of his enterprise and received the blessing of the church."2

When the preparations were completed in August 1066, events started to gather momentum. King Harold had mobilized his forces for fear of invasion and held them in a state of constant alarm. In September 1066, Harold was surprised by the invasion of a Norwegian enemy fleet under the leadership of Harold Hardrada, King of Norway. The Norwegians landed on the north-eastern shores of England, far away from the Anglo-Saxon army. Soon the invaders were marching through Northumbria and Yorkshire. Harold was now engaged in battle sooner than he thought, for he led his men northwards, straight towards the Norwegian army. The armies met at Stamford Bridge near York. The Anglo-Saxon victory on 25 September 1066 was bloody, but decisive. When the battle was over and the surviving Norwegians were allowed to embark their ships and sail away, they needed only twenty-four of their former two to three hundred ships.

Only two days after the battle at Stamford Bridge, due to favourable weather conditions, William decided that the time had come to set sail for England. He and his army of up to 15,000 soldiers crossed the Channel and landed at Pevensey without meeting any resistance. When news of William's landing reached King Harold, he rushed from the North to meet his enemy. But Harold's forces had been worn out by months of constant alarm, by the battle against the Norwegians and the restless troop movements.

On 14 October 1066, the two armies met at a place called Battle near Hastings in Kent. Harold's forces held an advantageous position on a hill that could easily be defended. The English infantry formed a wall of shields against the attacking Normans, but after hours of severe fighting and heavy casualties, the Norman archers and the cavalry had worn out the English soldiers. Near dusk, at the close of the day, the Normans performed a last feigned attack which lured the remaining English forces down the hill in pursuit of the supposedly fleeing Normans. But the Normans turned around and destroyed their pursuers in the open field. Suddenly, Harold, the Anglo-Saxon king, fell to the ground with an arrow through his eye. He died immediately.

The battle had been won by the Normans, William's rival Harold together with many of his vassals were dead, and the English army was extinguished. Still, William's most urgent obligation was to secure his still precarious position in a country that had not yet been fully conquered. For that purpose, he had to build fortified bases in the southern regions of England and to man them with units of his army under the leadership of loyal vassals. A determined and organized resistance from other Anglo-Saxon nobles never materialized, and eventually, English earls, archbishops, and representatives of cities submitted to William. On Christmas Day 1066, the Conqueror was crowned in Westminster Abbey by the archbishop of York. Five more years went by until he gained control of the country, defeating local insurrections.

1066 - The Battle of Hastings Sponsored / external links

1066: The Year of the Conquest

Hastings 1066 (Revised Edition): The Fall of Saxon England

The aftermath of 1066

The Norman conquest and the immigration of larger Norman-French contingents had a profound impact incomparable to that of any other conquest in history. Many of the changes brought about by the Normans were fundamental.

Firstly, the Anglo-Saxon landowning magnates, if they had not died in the battle of Hastings, lost their lands due to confiscation. Norman barons profited heavily from this, for they took possession of the seized lands. The Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical elite was also replaced with Norman-French candidates.

In 1075, eight out of twenty-one abbots were already Normans, and in 1087, only two English bishops (St. Wulfstan of Worcester and Giso of Wells) were in position and authority. Cloisters and abbeys were founded and staffed with Norman French monks, schools were established where Norman-French replaced Latin as the standard language of learning.

In 1086, one year before his death, William ordered that a survey should be carried out recording what each landowner in England held in land and livestock. This famous survey, the Domesday Book, gives us a detailed account of the distribution, the size, and the worth of land held by each landowner. It also proves that the post-conquest population, at least for the first two decades after 1066, was still strictly divided into subdued Anglo-Saxons ('Anglici' or 'Angli') and victorious Norman-French ('Francigeni').

A more or less strict social and linguistic separation of Norman-French speaking upper and Old English speaking lower classes was upheld throughout the eleventh century.

The language of the conquerors, Norman French, became the language of the court and the government. Norman-French literature also began to flourish under royal and noble patronage. While Latin and French were used by clerks and clergy, the majority of the population continued to speak the lingua plebis Old English.

The fact that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was continued in Old English up to 1154 may serve as proof of the tenacity of Old English. But during the twelfth century, due to intermarriage, further immigration and social interplay, the two social groups started to assimilate, adapting to each other's culture and language. For example, there were some who picked up Norman-French (e.g. merchants, carpenters, stewards, or bailiffs working for Norman lords), while some Normans learned English (e.g. landlords who had to deal with their English tenants etc.).

We can presume that the bilingual share in the population rose steadily. Even the attitude of the Norman-French nobility towards England gradually changed. In the eleventh century, the Normans had looked upon England as a newly conquered province, while they remained emotionally and psychologically tied to their Norman motherland. Under William the Conqueror, the Kingdom of England and the Dukedom of Normandy had been united into one great kingdom under one ruler.

When William died in 1087, he distributed his possessions according to custom: his eldest son Robert Curthose succeeded him to the dukedom of Normandy, while his second son, William II Rufus, gained England, his father's recent conquest.

As long as the kingship of England and the dukedom of Normandy were in two separate hands, there were conflicts of allegiance. The Norman vassals and barons had possessions on either side of the Channel, so they owed allegiance to both William II Rufus as king of England and to Robert, Duke of Normandy. Odo of Bayeux (1036?-1097) paraphrased the dilemma this way: "How can we give proper service to two distant and mutually hostile lords'! If we serve Duke Robert well We shall offend his brother William (Rufus) [...], On the other hand, if we obey King William, Duke Robert will deprive us of our patrimonies in Normandy."3

This situation was resolved when, towards the end of the eleventh century, William Rufus gained possession of Normandy, uniting the dukedom and the kingship in his hands, thus enabling his vassals to pay homage to one single lord The kingship and the dukedom remained in one hand after William Rufus' death in 1100.

Due to their possessions on the continent, English kings got more and more involved in taking care of their French territories, especially when they intended to expand their realm on the continent, For example, King Henry II Plantagenet (1154-1189), William the Conqueror's great-grandson, spent two-thirds of his life in France. He ascended the throne in 1154 and, through a favourable marriage with Eleanor of Aquitaine, had increased his realm enormously. Eleanor's dowry consisted of vast territories, so that Henry ruled not only over England, but also over the complete west of France (Normandy, Brittany, Anjou, Maine, Poitou, Aquitaine, and Gascony). He became more powerful than the French king himself, who was actually Henry's overlord.

The tensions between the French overlord and vassal increased under Henry's sons and successors, Richard I Lionheart (1189-1199) and John Lackland (1199-1216). After Richard Lionheart's death in 1199, his younger brother, John Lackland, succeeded to the English throne. His was a rather unfortunate reign, for it was under his kingship that, apart from some territories in the south-west of France, the English crown lost the most important part of its continental possessions. In 1204, French King Philip August confiscated the dukedom of Normandy due to a marriage dispute which involved King John in his capacity as duke of Normandy. One of Philip August's vassals, count Hugh of Lusignan, had been betrothed to Isabelle of Angoulème. But when King John saw her, he violently fell in love with her and married her on the spot. With this act, John had broken a pre-arranged marriage, and he was summoned before the court of Philip August for this injustice. But King John ignored the summons to appear before the French royal court, and Normandy and Brittany were lost. This had far-reaching consequences for the Anglo-Norman nobility. The Anglo-Norman barons and landholders were now faced with the choice of either retaining their continental or their English possessions. The course of separation greatly accelerated under John's successor, Henry III. In 1244, French King Louis IX confronted all Anglo-Normans who had possessions both in England and in France with the decision of choosing one overlord, either the French or the English king. Shortly after 1250, the process of separation was complete, and the nobility had split itself and their estates into French and English.

In 1259, Henry III completely cut off the ties with the old possessions by renouncing all claims on Normandy, Maine, Anjou, Poitou and other territories. Due to political developments and despite their Norman origins, the nobility in England eventually started to feel like Anglo-Norman. They had become estranged from their ancestral estates on the continent, and they eventually came to think of England as their motherland. The foundation for the development of a sense of national identity (and a joint “national” language and literature) had been laid in the thirteenth century.

But despite these signs of assimilation among the nobility, the dominant influence of French on government, parliament, education, culture, and literature still prevailed. For the second time after the Conquest, ever since Henry III had married Eleanor of Provence, a renewed influx of French - most prominently the queen's Provençal relatives - into England began. Due to Henry's generosity, many of the Queen's French relatives found a comfortable income at court, as vassals, clerics, or counsellors to the king. But his barons did not share his generosity. In 1258, a baronial reform movement opposed the king under the leadership of Earl Simon de Montfort. Although the demands seemed politically motivated, the question of the French “foreign” favourites as counsellors to the king also played a significant part in it.

From 1258 to 1263, England was at the brink of civil war. As the quarrelling factions could not compromise, war broke out in 1264. The decisive battle of Lewes in May 1265 saw the victory of the baronial opposition, and King Henry III was held prisoner. But the tide was turning in favour of the monarch. Another battle in 1265 ended Simon de Montfort's life and his opposition. This episode may serve as an indication as to how far the English and the Anglo-Normans had already fused.

The aftermath of 1066 External affiliate links

England and its Rulers: 1066 - 1307

1066 and All That: A Memorable History of England

A Social History of England, 1200-1500